Would every Syrian asylum seeker become another Naim Süleymanoğlu?

All the news stories over the past few months stir our emotions. Emotions take the lead in the debates on the current state of affairs in the country. Syrians rank high among the critical issues reigned by emotions. We face a migratory influx comprising millions of people that leave their homes behind and go seek a new life that promises safety and possibly higher welfare. The government spokesperson said a few days ago that there are 2.2mn Syrians in Turkey. This migration flow started in 2011. We assumed back then that the inflow was temporary and the neighbors we hosted would return home once the situation in Syria was normalized. But as we approach the end of 2015, the dominant viewpoint today is that Syria will never recover to its old self, that millions have lost their homes into thin air and that they are now bound to get themselves new lives outside Syria.

Under the circumstances, it is high time we, the folks in Turkey, start exploring uncharted territories and making decisions based on reason rather than emotions. That said, we’re all aware of what has become of politics in our country and the atmosphere brought about by elections held one after another. An overview of the studies on the issue suggests that the state of affairs in the academia isn’t any better. Some organizations engage in well-meaning initiatives but most are simply palliative in their approach. There seems to be no comprehensive framework as to how the old 76mn population and the new 2mn newcomers can integrate into a cohesive whole.

I would like to make three points on the issue of Syrian asylum seekers in this article, with the hope of making a contribution to a debate mediated not by emotions but rather reason.

Point 1: In order to be able to discuss the effects of such a massive migration inflow on the country, we need to have a big picture regarding the meaning of Syrians for our lives and our economy. There seem to be bits and pieces of portrayals around, but most are bleak. Rents rise, inflation creeps up in some cities, some companies hire Syrian labor for peanuts, some Syrians open shops, evade taxes and create unfair competition, ghettoization is rampant, security problems emerge. And of course, the images of the Syrians that don’t want to stay in Turkey but go to Europe instead; and of the terrible tragedies that befall them. Each of these is a different news story, a different picture. But we will not be getting the big picture if we simply put them together.

Another way to see the big picture is to divert our gaze to other countries. For instance, as our academia runs around in circles, sober and interesting studies are carried out in other countries on the economic impact of migration flows. For example, according to a study[1] that analyzes trade, investment and migration flows among 136 countries over the past two decades, the entry of 15,000 qualified immigrants to an average country improves the chances of the country to add a new sector to its export portfolio by 15%. The same study suggests that the arrival of each employable immigrant corresponds to an inflow of $30k in foreign investments, whereas a well-educated immigrant corresponds to $160k. The primary channel of effect that the study bases itself on is that, along with migration, the necessary skills and know-how to produce a particular product are also transferred from one country to another.

According to a field study by AFAD in 2013, half of the Syrians that have come to our country are in the working age range (the 19-65 age interval). 10% of this group have university, 10% high school and 20% secondary school diplomas. 40% are either primary school graduates or literate, while 20% are illiterate.[2] According to these data, over the past four years, 500,000 employable average-skilled, and 200,000 high-skilled Syrians have immigrated to our country. According to the framework cited above, this corresponds to a foreign direct investment inflow of $47bn (whereas Turkey received an annual $13bn foreign investment inflow in the 2011-2014 period.)

Obviously this calculation of foreign direct investments amounting to $47bn merely indicates the potential. The capacity to mobilize this potential depends on whether our government has a solid vision for adaptation and integration. The prerequisite for that is a wholesale change in the policy framework that we designed in the 1950s, which considers Syrians (and anyone else who comes from the east) not as immigrants but simply as asylum seekers. We can create new horizons neither for ourselves nor for the Syrians with this transitory perspective. Furthermore, if we stop basing our new immigration policy on just a humanitarian aid perspective but endorse it with a policy framework on industry and employment, perhaps we may begin to resort to reason rather than emotions on the question of what the bigger picture should look like.

As a second point, I’d like to focus on the possible effects that Syrian asylum seekers may have on the Turkish economy. I wonder if the skill sets, experiences, foreign market connections etc. necessary to produce particular products have come to our country along with the migration inflow. There are, unfortunately, no concrete studies on this issue. But this we know: More than half of the Syrians in our country have come from Aleppo and nearby settlements, i.e. the heart of the economy in former Syria where industrial activities were concentrated. The newcomers reportedly include investors who are well familiar with and connected to the Middle Eastern market. Besides, numerous investors and small businesses are also known to have relocated not just their families but also their capitals and businesses to Turkey.[3] Thanks to these companies, Turkey’s exports to Syria, which had dropped to nothing in the wake of the war, recovered rapidly in 2013 and 2014 to their pre-war levels. News stories on the media point out that there are numerous companies that have relocated from Aleppo to Gaziantep and Mersin in particular.[4]

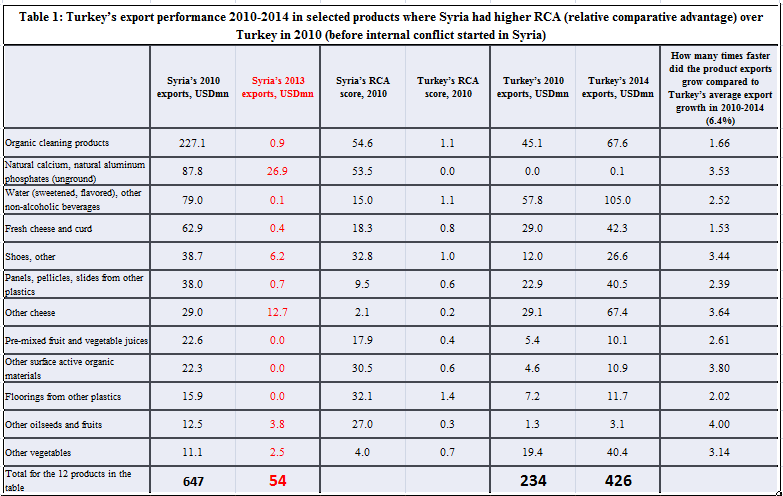

Could this channel of effect bear weight for the future of the Turkish economy? Let’s take a look at the table below. It offers interesting data on twelve different products. What is peculiar about these twelve products is that Syria had significant comparative advantage over Turkey in the production of these products in 2010, before the civil war broke out.[5] Syria’s exports in these twelve products in 2010 amounted to $650mn, 5% of its total exports, whereas Turkey’s exports of the same products in 2010 stood at a mere $234mn. This means Turkey’s export capacity for these twelve products prior to the war was only one third of that of Syria. However, with the onset of the civil war in Syria, which obstructed productive activity, the exports of the country slid sharply by more than 90% over three years to $50mn.

Here’s the interesting point: From 2010 to 2014, while Turkey’s aggregate exports rose by 38%, its exports in these twelve products doubled to $426mn, i.e. tenfold of Syria’s exports. And the growth in the export rate of each product over the past four years doubled, tripled, or quadrupled Turkey’s average export growth (see the rightmost column in the table). These products include organic cleaning products, shoes and cheese.

Source: BACI, UN Comtrade TEPAV calculations at the HS 1992 6th level.

It is obviously impossible to say just by looking at this single table whether the rise in these twelve products are thanks to the Syrian asylum seekers or Turkish companies’ tact to fill the void left by the Syrians. But here’s the one conclusion of this table: Syria had capacities in certain areas and these are no longer within Syria. We don’t know how much of these capacities have been transferred to Turkey, because sadly we don’t have a centralized database on asylum seekers. We don’t know the education levels or the professions of the 2.2mn Syrians in our country. Even if we did, it is another question as to how prepared we are to make good use of these capacities anyway.

The third and final point is about the tragedies faced by the asylum seekers we see in Edirne today. If we had the habit of contemplating the issue of economic growth on a local basis, we might hear different news from Edirne today. There are thousands of people who want to transit to the European Union via Edirne. The folks of Edirne could have made a positive contribution to their own futures too, if they tried to keep these people there in addition to simply providing humanitarian aid. The reason for this is the fact that one of Edirne’s most pressing problems today is gradual decline in the number of qualified young people who live and work in this border province. Let me elaborate a bit on that: Edirne, once an Ottoman capital and a city that received and integrated huge masses of immigrants from Russia, the Balkans or Spain for centuries, needs a young population today, because the well-educated youth of Edirne are bound to live in Istanbul. Therefore, Edirne’s economic dynamism weakens by the day, with the urban economy growing more and more dependent on a single university, a single military post and somewhat on the domestic tourist flows. Two important districts of Edirne, Keşan and Uzunköprü, also have very high economic potentials, but lack the young population to fulfil that potential.

I wish our cities like Edirne or even our districts like Uzunköprü and Keşan, facing the problem of dwindling economic dynamism and population they face today, had been declaring the work permit quotas that European countries, appallingly, declare at a meager level of a couple of thousands. That would have meant that the burden and the opportunities posed by asylum seekers would be distributed in a more even, equitable and (in terms of economic growth prospects) strategic manner across the entire country, rather than just the ten cities on the border.

[1] Bahar, D. Rapport H (2015) “Migration, knowledge diffusion and the comparative advantage of nations” http://scholar.harvard.edu/files/dbaharc/files/br_migration.pdf

[2] AFAD (2013) Syrian Asylum Seekers in Turkey, Report on 2013 Field Study Results.

[3] ORSAM & TESEV (2015) Report on the Impact of Syrian Asylum Seekers on Turkey.

[4] T24, “Suriyeliler İşlerini Türkiye’ye taşıdı, Almanları Solladılar, 17 August 2013, http://t24.com.tr/haber/Suriyeliler-islerini-turkiyeye-tasidi-almanlari-solladilar,237155

[5] We figure this out by calculating the RCA (revealed comparative advantage) score for both countries. RCA is an indicator calculated by comparing the market share of a certain product a country exports to the market share of the aggregate exports of the country.